Khosrau II

| Khosrau II | |

|---|---|

| King of Persia | |

| Gold coin with the image of Khosrau II | |

| Reign | Persia: 590 AD to 628 AD |

| Born | unknown |

| Birthplace | Ctesiphon |

| Died | February 28, 628 |

| Place of death | Ctesiphon |

| Predecessor | Hormizd IV |

| Kavadh II | |

| Successor | Kavadh II as King of Persia and Byzantine Emperor Heraclius as King of Kings |

| Consort | Shirin, Miriam/Maria |

| Father | Hormizd IV |

| Religious beliefs | Zoroastrianism |

Khosrau II (Khosrow II, Chosroes II, or Xosrov II in classical sources, sometimes called Parvez, "the Ever Victorious" – in Persian: خسرو پرویز) was the twenty-second Sassanid King of Persia, reigning from 590 to 628. He was the son of Hormizd IV (reigned 579–590) and grandson of Khosrau I (reigned 531–579).

Contents |

Biography

Personality and skills

Khosrau II was inferior to his grandfather in terms of proper education and discipline. He was haughty, cruel, and given to luxury; he was neither a warrior-general nor an administrator and, despite his brilliant victories, did not personally command his armies in the field, relying instead on the strategy and loyalty of his generals. Nevertheless Tabari describes him as:

Excelling most of the other Persian kings in bravery, wisdom and forethought, and none matching him in military might and triumph, hoarding of treasures and good fortunes, hence the epithet Parviz, meaning victorious.[1]

According to legend, Khosrau had a shabestan in which over 3,000 concubines resided.[1]

Ascension to the throne

Khosrau II was raised to the throne by the same magnates who had rebelled against his father Hormizd IV. Soon after being crowned, Khosrau had his father blinded, then executed. However, at the same time, General Bahram Chobin had proclaimed himself King Bahram VI (590–591), exemplifying Khosrau's difficulty in maintaining control of his kingdom.

The war with the Byzantine Empire, which had begun in 571, had not yet come to an end. So, Khosrau II fled to Syria, and subsequently to Constantinople where the Emperor Maurice (582–602) agreed to assist Khosrau in regaining his throne. In return, the Byzantines would re-gain sovereignty over the cities of Amida, Carrhae, Dara, Nisibis and Miyafariqin (Middle Persian Miyān Pārgin). Furthermore, Persia was required to cease intervening in the affairs of Georgia and Armenia, effectively ceding control of Lazistan to the Byzantines.[2][3] A large percentage of the leading bureaucrats, administrators, governors, and military commanders, along with the majority part of the Persian military, acknowledged Khosrau II as the King of Persia. Therefore, in 591, Khosrau returned to Ctesiphon and defeated Bahram VI in Azerbaijan. Bahram fled to the Turks of Central Asia, but he was eventually murdered by them. Then, peace with Byzantium was concluded. For his aid, Maurice received the Persian provinces of Armenia and Georgia, and received the abolition of the subsidies which had formerly been paid to the Persians.

Military exploits and early victories

Towards the beginning of his reign, Khosrau II favoured the Christians. However, when in 602 Maurice was murdered by his General Phocas (602–610), who usurped the Byzantine throne, Khosrau launched an offensive against Constantinople, ostensibly to avenge Maurice's death, but clearly his aim included the annexation of as much Byzantine territory as was feasible. His armies invaded and plundered Syria and Asia Minor, and in 608 advanced into Chalcedon.

In 613 and 614 Damascus and Jerusalem were besieged and captured by General Shahrbaraz, and the True Cross was carried away in triumph. Soon afterwards, General Shahin marched through Anatolia defeating the Byzantines numerous times, and then conquered Egypt in 618. The Romans could offer but little resistance, as they were torn apart by internal dissensions, and pressed by the Avars and Slavs, who were invading the Empire from across the Danube River.

Khosrau's forces also invaded Taron at times during his reign.[4]

Richard Nelson Frye speculates that one major mistake of Khosrau II, which was to have severe consequences in the future, was the capture, imprisonment, and execution of Nu'aman III, King of the Lakhmids of Al-Hira, in approximately 600, presumably because of the failure of the Arab king to support Khosrau during his war against the Byzantines. (Nu'aman was crushed by elephants according to some accounts.) Afterwards the central government took over the defense of the western frontiers to the desert and the buffer state of the Lakhmids vanished. This ultimately facilitated the invasion and loss of Lower Iraq less than a decade after Khosrau's death by the forces of the Islamic Caliphs.[5]

Turn of tides

Ultimately, in 622, the Byzantine Emperor Heraclius (who had succeeded Phocas in 610 and ruled until 641) was able to take the field with a powerful force. In 624, he advanced into northern Media, where he destroyed the great fire-temple of Ganzhak (Gazaca). Several years later, in 626, he captured Lazistan (Colchis). Later that same year, Persian general Shahrbaraz advanced to Chalcedon and attempted to capture Constantinople with the help of Persia's Avar allies. His maneuver failed as his forces were defeated, and he withdrew his army from Anatolia later in 628.

Following the Khazar invasion of Transcaucasia in 627, Heraclius defeated the Persian army at the Battle of Nineveh and advanced towards Ctesiphon. Khosrau II fled from his favourite residence, Dastgerd (near Baghdad), without offering resistance. Meanwhile, some of the Persian grandees freed his eldest son Kavadh II (he ruled briefly in 628), whom Khosrau II had imprisoned, and proclaimed him King on the night of 23-4 February, 628.[6] Four days afterwards, Khosrau II was murdered in his palace. Meanwhile, Heraclius returned in triumph to Constantinople and in 629 the True Cross was returned to him and Egypt evacuated, while the Persian empire, from the apparent greatness which it had reached ten years ago, sank into hopeless anarchy. It was overtaken by the armies of the first Islamic Caliphs beginning in 634.

Muhammad 's letter to Khosrau II

Khosrau II (Arabic كسرى) is also remembered in Islamic tradition to be the Persian king to whom Muhammad had sent a messenger, Abdullah ibn Hudhafah as-Sahmi, along with a letter in which Khosrau was asked to preach the religion of Islam. In Tabari’s original Arabic manuscript the letter to Khosrau II reads:

بسم الله الرحمن الرحيم

من محمد رسول الله الى كسرى عظيم الفرس . سلام على من اتبع الهدى و آمن بالله و رسوله و شهد ان لااله الا الله وحده لاشريك له و ان محمد عبده و رسوله. ادعوك بدعاء الله، فانى رسول الله الى الناس كافة لانذر من كان حيا و يحق القول على الكافرين. فاسلم تسلم . فان ابيت فان اثم المجوس عليك .

English translation:

In the name of God, Most Gracious, Ever Merciful

From Muhammad, Messenger of God, to Chosroes, Ruler of Persia. Peace be on him who follows the guidance, believes in God and His Messenger and bears witness that there is no one worthy of worship save God, the One, without associate, and that Muhammad is His Servant and Messenger. I invite you to the Call of God, as I am the Messenger of God to the whole of mankind, so that I may warn every living person and so that the truth may become clear and the judgement of God may overtake the disbelievers. I call upon you to accept Islam and thus make yourself secure. If you turn away, you will bear the sins of your Zoroastrian subjects.

The Persian historian Tabari continues that in refusal and outrage, Khosrau tore up Muhammed's letter and commanded Badhan, his vassal ruler of Yemen, to dispatch two valiant men to identify, seize and bring this man from Hijaz (Muhammad) to him. Meanwhile, back in Madinah, Abdullah told Muhammad how Khosrau had torn his letter to pieces and Muhammad's only reply was, "May his kingdom tear apart", and predicted that Khosrau's own son shall kill him. The narration carries on with accounts of their encounter and dialogue with Muhammad and conversion of Badhan (Bāzān) and the whole Yemenite Persians to Islam subsequent to receipt of shocking tidings of Khosrau’s murder by his own son, Kavadh II.[7]

In other chapters Tabari gives two more detailed accounts. One tells of how Islam had been presented in three subsequent years to the Persian monarch (Khosrau II) by an angel of Allah while he had refused the whole time; and the other on how Khosrau II orders Persians thrice to construct a dam and iwan on the Tigris river with untold toil and outlay with exact intervals of 8 months, only to see each one break once Khosrau himself embarked it to celebrate its construction.[1]

Criticism of Muslim accounts

Leone Caetani, in his ten-volume book Annali dell' Islam that was based on the research presented by German scholar Hubert Grimme in Das Leben Muhammed, dismisses the notion that Muhammad ever sent any envoys to rulers of neighboring kingdoms, much less received any responses; Caetani also refutes that whatever is told or written in this regard is merely a myth fabricated by the Islamic Caliphate many years after Muhammad's death.

In his work, Caetani alludes to a number of facts to prove his point of view:

- All the information from historical sources (Persian, Armenian, Georgian, Syriac, Egyptian, etc.) suggest that Sassanid court ceremonies have been the most intricate in the ancient world, and among the most elaborate of such formalities had been granting audience to individuals seeking to meet with the Sassanid Shahanshah. Ibn Khordadbeh in Kitāb al-Masālik w’al- Mamālik describes how each and every foreign envoy had to submit his message to the marzban of the bordering province (in this case: vassal kingdom of Al-Hirah) whose bureaucratic system would evaluate the contents of the message and the envoy’s purpose of audience with the monarch. Most often, the envoy would be accommodated in an envoys' border lodge for a certain period of time awaiting such decision. The envoy was then escorted to the capital only if the message was considered pertinent for the court in Ctesiphon or if the said marzban would not be capable of resolving a much complicated diplomatic issue. In all other cases, the embassy was refused.

- Even second-class marzbans and spahbods were not exempted from such cumbersome formalities, not to mention an envoy arriving from a relatively obscure source to the Sassanid court; and even then during the royal audience, one had to observe certain strict customs such as kissing the floor, covering one’s mouth by panam (Persian: پنام), conversing with particular etiquette, and carefully avoiding approaching Shahanshah’s throne.[8]

- Caetani deduces that bearing in mind the impertinence and assertive tone of the message, Sassanid administrators must, in all probability, have denied such audience.

- As regards to Khosrau’s challenging dam project on the Tigris, Caetani elaborates that the years 6 and 7 AH (627-628 AD) had been the most tumultuous periods of the Sassanid era: Heraclius was closing in on gates of Ctesiphon following his decisive victory at Nineveh; the treasury was nearly exhausted and the empire itself was weakening.

- It would then be negligence towards historical facts to imagine an unstable monarch triply commencing the ambitious task of “untold toil and outlay” with a bankrupted treasury and lack of safety on the Tigris riverside.[9]

- Caetani also hints at the fact that none of the Persian historical chronicles recording the ending years of the Sassanid era — specifically khodaynamehs (Persian: خداينامه meaning “book of lords”) that later became sources of information for Ferdowsi and other scientists and historians such as Birouni, Tha'alibi, Masudi, Isfahani – mention such an embassy, and whatever narrated in this context is exclusively limited to Arabic sources, while Iranians have never been aware of this matter.

Furthermore, there is no reference to these letters in Latin, Greek, Armenian, Georgian, or Syriac sources, signifying that these letters — including the ones dispatched to Heraclius, Ashama ibn Abjar and Patriarch of Alexandria- for all non-Arabic sources, are entirely unheard-of.[10]

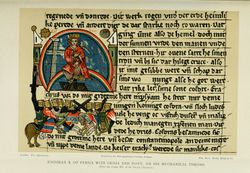

In art

The battles between Heraclius and Khosrau are depicted in a famous early Renaissance fresco by Piero della Francesca, part of the History of the True Cross cycle in the church of San Francesco, Arezzo. Khosrau has been painted in the Ajanta Frescoes.

|

Khosrau II

|

||

| Preceded by Hormizd IV |

Great King (Shah) of Persia 590 –628 |

Succeeded by Kavadh II |

See also

- Shirin Beloved wife of Khosrau

- Khosrow and Shirin A Persian love story depicting a ménage à trois between Khosrau and Shirin as king and queen, and Farhad as Shirin's lover

- Barbad Khosrau's favorite court musician

- Shabdiz Khosrau's highly admired horse

- Non-Muslim interactants with Muslims during Muhammad's era

- Muqawqis, Ruler of Alexandria

- Behistun inscription

- Behistun palace

- Babai the Great

References

Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). "Chosroes". Encyclopædia Britannica (Eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). "Chosroes". Encyclopædia Britannica (Eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press.- Edward Walford, translator, The Ecclesiastical History of Evagrius: A History of the Church from AD 431 to AD 594, 1846. Reprinted 2008. Evolution Publishing, ISBN 978-1-889758-88-6. [1] — a primary source containing detailed information about the early reign of Khosrau II and his relationship with the Romans.

- Continuité des élites à Byzance durante les siècles obscurs. Les princes caucasiens et l'Empire du VIe au IXe siècle, 2006

Footnotes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Muhammad ibn Jarir al-Tabari, History of the Prophets and Kings, vol. 2

- ↑ Dinavari, Akhbâr al-tiwâl, pp. 91-92;

- ↑ Ferdowsi in Shahnameh affirms the same conditions put forth by Maurice.

- ↑ Armenian Folk Literature, John Mamikonean's History of Taron

- ↑ Richard Nelson Frye, The History of Ancient Iran, p 330.

- ↑ According James Howard-Johnston in his notes to The Armenian History attributed to Sebeos (trans. R.W. Thomson; Liverpool: University Press, 1999), p. 221

- ↑ Muhammad ibn Jarir al-Tabari, History of the Prophets and Kings, vol. 3

- ↑ For a comprehensive research about Sassanid court ceremonies and bureaucratic procedures, you may refer to Arthur Christensen’s “Sassanid Persia”

- ↑ Leone Caetani, Annali dell' Islam, vol. 2, chapter 1, paragraph 45-46

- ↑ Leone Caetani, Annali dell' Islam, vol. 4, p. 74